I'm a father of three from Sydney, a Product Director and a Product Coach. I write about product management and run the Product Manager community.

Subscribe to receive digest emails (1 per month).

Info

Posts with Business tag.

-

Product Managers wait for clarity that never arrives.

They expect the strategy doc to have the answers. But nothing lands. Just more PowerPoint slides.

Because the higher up you go, the blurrier it gets. Goals get loftier. Language gets vaguer. No one wants to be wrong. So they delay, they decorate confusion with buzzwords. It feels smart but it isn't clear.

The best Product Managers don't wait. They start shaping. They turn fuzzy goals into concrete next steps. They don't chase alignment. They chase decisions. They poke holes (even when it creates discomfort). They write the draft no one asked for. They map the fog, not run from it.

Because anyone can follow a plan. But great Product Managers can make one. They stop asking “What's the direction?” and start saying “Here's what I'm seeing - poke holes in it”

-

Takeaways: From Jira Junkies to Profit Prophets

📘 Most product teams don't understand revenue. They know user needs, but not what closes a deal. They talk to customers, but rarely prospects. That's a big gap. Product decisions often ignore willingn... Read more -

Change doesn't come from a reorg or a new title on a slide.

It comes from the person who says, “This isn't good enough,” and then does something about it. Quietly. Consistently. Without waiting for permission. That's what standards are - choices made over and over, even when they're inconvenient, invisible, or unpopular.

The real power isn't in setting high standards. It's in holding them when no one's watching. When shortcuts are easier. When mediocrity is the norm. That's where most people cave. They look around, see no one else pushing, and assume it's not worth the fight.

But it is.

Every time someone sticks to their standard, it makes space for someone else to do the same. Not with big declarations, but with small acts of defiance against the average.

The more people who hold the line, the easier it becomes to draw a new one. Holding the line isn't easy - but a product management coach can support you in leading with consistency. -

Some tech teams think their job starts when the requirements arrive.

But that mindset turns them into delivery machines - waiting for Jira tickets like orders at a café. The real value isn't in ticking off tasks. It's in shaping them. Working with product managers, not for them.

Because PMs aren't there to write task lists. They're commercial thinkers. They're shaping strategy, pushing customer insight, and holding the big picture. They don't need followers. They need partners.

Do less: waiting for answers.

Do more: collaborating to understand the “why.”

That's how you build better products - and better teams.

-

Takeaways: Superhuman's secret to success

📘 The early Superhuman team did something most founders would find wild: they ignored most customer feedback. Not because it wasn't useful - but because most users weren't the right users. To find pro... Read more -

Validation Comes After Launch

You can't validate a product with opinions.

People love to be nice. They'll tell you what you want to hear. “I'd buy that.” “Sounds awesome.” “I'd totally use it.” They're not lying to be cruel. They'... Read more -

Increasing Capacity by 37signals

📘 You don't need more people to do more work. Most teams slow down as they grow. Speed and capacity come from clarity, cohesion, and trust - not headcount. A smaller, sharper team gets more done with ... Read more -

You see the promises fall flat.

You watch them dodge decisions, fumble delegation and ignore the weight of a frustrated team.

It feels like yelling into a void.

But you still show up. Not for them - for the people beside you. You lift the work with your peers. You raise the bar. You protect the standard. You become the person who cares when no one else does. Even with a ceiling pressed down on your growth, your pride, your pay - you stay. You find meaning in the work itself. Because the work matters.

But ceilings don't stay soft forever. Sometimes they turn to concrete.

The team starts shrinking from bold to bitter. Feedback goes quiet. Energy fades. You feel it in your bones: you're no longer growing, just grinding.

That's when the question hits - how long do I keep pushing when it's clear no one's listening?

As I've said before: “The standard you walk past is the standard you accept.”

That applies to toxic culture. But it also applies to dead-end leadership.

So if your ideas can't rise, if your potential gets capped, if staying means shrinking.

There's only one move left.

Leave. Before they forget what you're capable of. Before you do. -

Yearly performance reviews aren't good. You have probably seen neglected and outdated goals in performance reviews in your career. They become irrelevant pretty quickly. Worse, they do more harm than good.

The best teams ditch the annual review cycle. Instead, they focus on:- Continuous feedback

- Small, actionable coaching

- Growth over grades

- Space for trial, error and mastery

Solid teams that don't wait a year to improve. They get better every day. -

Messy teams don't mean broken teams.

They're just growing. Growth kicks off the “storming” phase - overlaps, confusion, delays. Everyone's working hard, but everything feels slow.

That's not a motivation problem. It's an ownership problem.

When no one's clearly accountable, things fall between the cracks. Work stalls. Friction builds. Blame starts to creep in. But assign clear ownership - name, scope, outcome - and everything changes. Now someone's driving. Now someone's finishing.

Ownership creates motion. Shared responsibility sounds nice, but it rarely works. When everyone owns something, no one owns anything.

So make it visible. Write it down. Who owns what. Why it matters. When it's due.

That's how work moves forward. Not with good intentions. With clear accountability. -

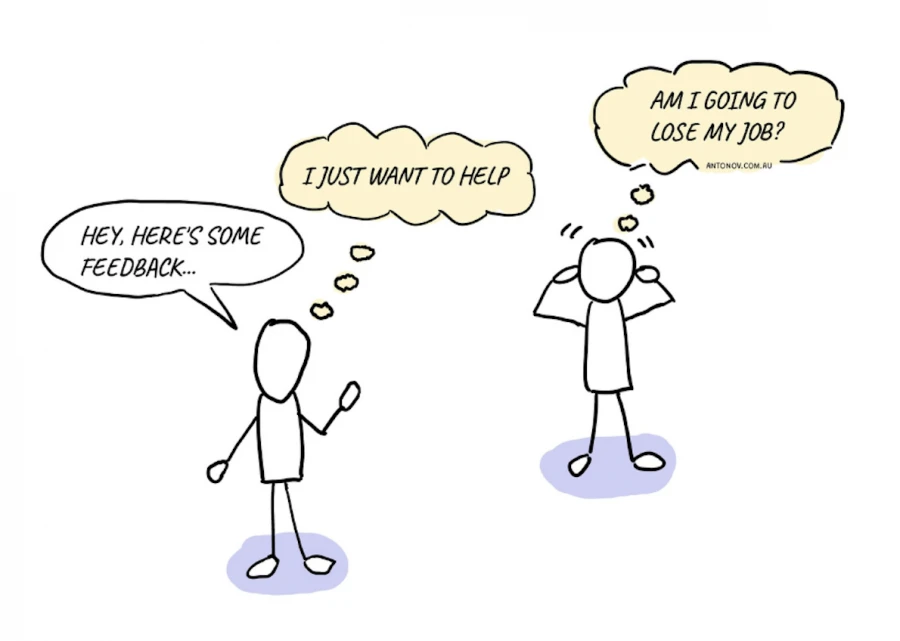

People think they're not getting feedback.

But they are - they just don't recognise it.

A simple way to fix this? Make it obvious. Instead of letting feedback blend into daily conversations, label it: “Here's some feedback for you.”

That small shift makes a big difference. -

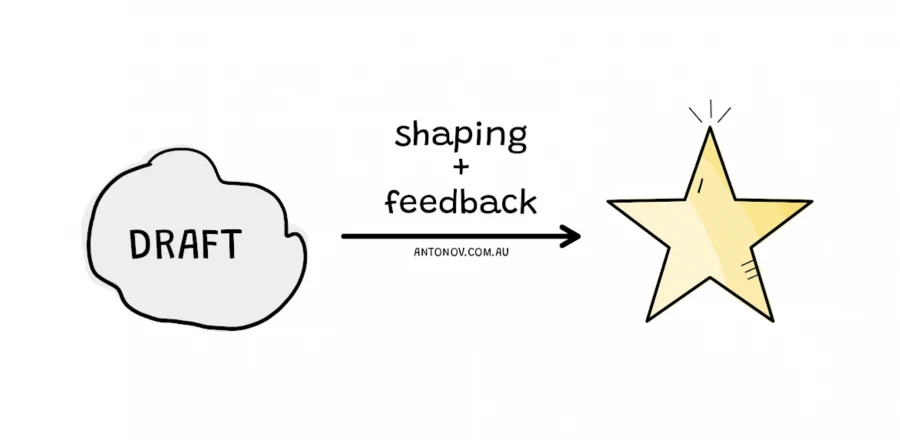

The point isn't to get it right. It's to get it moving. You shape, share, and sharpen through feedback. That's how the rough idea turns into something worth showing.

Start with a mess. End with a star.

What's shaping? See shaping the work. -

Feedback lands best when the walls are down.

But too often, it does the opposite. It raises shields. Because even when intentions are good, the words feel sharp. The tone feels off. And the brain - wired for survival, not nuance - reads threat where you meant support.

It doesn't matter how thoughtful or constructive the feedback is. If the other person is in defence mode, they won't hear a word of it. They'll hear judgment. They'll hear risk. They'll hear “you're not good enough.” That's why intention isn't enough. Clarity is what cuts through.

So be clear.

Not in a vague, corporate tone. In plain language. “You're doing well. I want to help you do even better.” Or, “This is something I wish someone told me earlier in my career - I think it might help.” You're not correcting.

Feedback delivered too late becomes irrelevant or awkward. Deliver it while the moment's fresh and the actions are remembered. But always with context. Always with care.

Because the goal of feedback isn't to win an argument. It's to build someone up without them feeling torn down.

If you're trying to improve how feedback lands, a product management coach can help you practise framing it in a way that actually builds trust.

Frame it right, and feedback becomes a shield. Not a weapon.

-

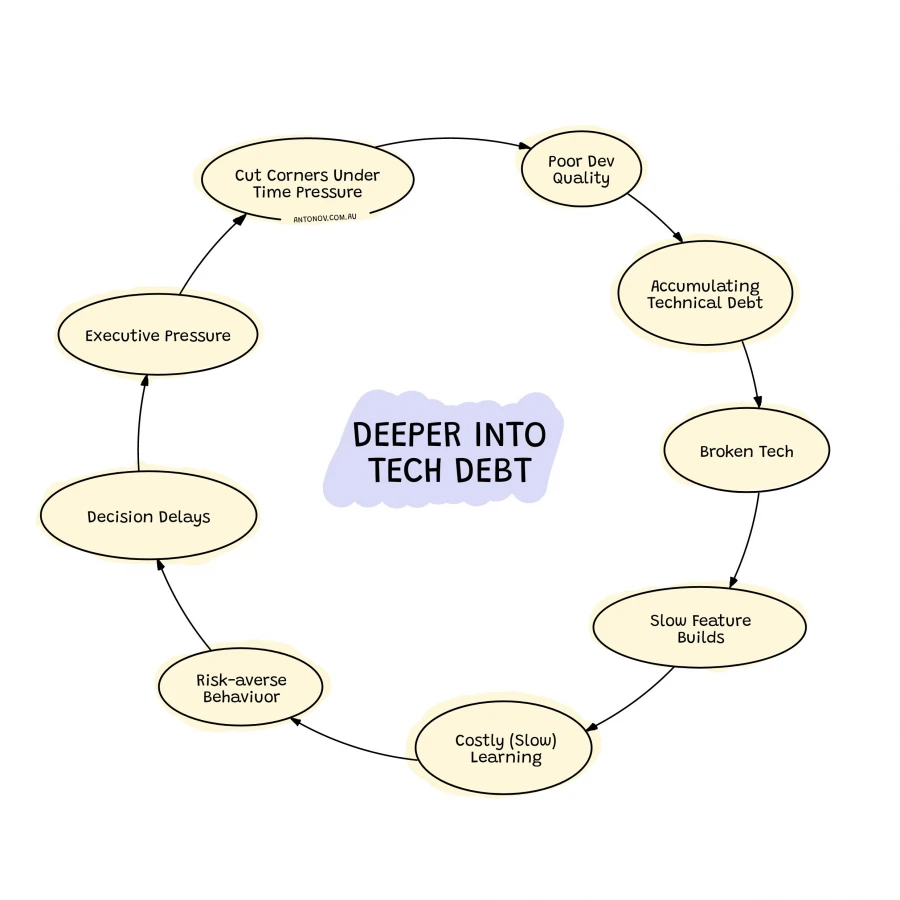

Like a snowball rolling downhill, technology debt simply gets bigger.

Cutting corners and patching things up work for a while. But eventually the codebase becomes a mess. Features take longer to build, and bugs pile up. The team becomes nervous about making changes. This triggers leadership demands speed, trapping everyone in a difficult cycle to break.

-

Brian Chesky’s new playbook

Everyone Must Row in the Same Direction

Clarity beats compromise. Instead of negotiating how to run Airbnb, Brian made a clear call: unify under one roadmap, one set of priorities, and one way of work... Read more -

No one starts with a perfect strategy. That's just not how it works.

You set a few goals, spot the obvious roadblocks and take your first steps. How about the rest you might ask? You figure it out along the way. Just keep an eye on the market and overall trends and adjust your strategy as needed. And yeah, unexpected problems will pop up. That's normal though. They aren't failures - just part of the process. Every setback teaches you something.

A plan points you in the right direction, but real clarity comes from doing the work. The teams that adapt, adjust, and keep moving - especially when things feel uncertain - are the ones that make real progress.

So don't wait for the “perfect” plan. Just start. You'll get there.

-

To build great products you need to start asking great questions.

A simple question: “What problem are we solving?” will shift a team's mentality from execution to purpose.

And you can feel the exact moment when task-doers start to solve problems.

It's when they talk less about delivery and shipping features and ask more about business challenges, user pain points and the market. That's when they stop taking orders - and start shaping work.

Questions fuel curiosity and curiosity drives collaboration. Teams that ask deeply create better products. -

Bob Moesta: How to find work you love

Stop Making Progress, Start Job Hunting

The moment career progress stops, job searching begins. Most people don't know how to find a better job because they don't know themselves. Moesta interviewed a... Read more -

Results First

Your first responsibility as a manager is to deliver results.

Not culture. Not vibes. Not endless check-ins. Results.

Too many new managers fall in love with the performance of management. They build ... Read more -

Centralised decision-making will always create bottlenecks. Sooner or later, this will prevent your company from growing.

Traditional and rigid organisations value hierarchy, and leaders often think they need to control every decision.

But this slows innovation, delays time to market, and prevents teams from learning.

Create a culture of ownership at every level. Empower your team to make decisions within their areas of expertise. Trust fuels faster progress.

Feel free to reach out: [email protected].